Why God Doesn't Exist, But Amida Buddha Does

A Monk's Encounter with a Philosophy That Sets Deities Free

A friendly note from the author: The title of this piece is intentionally a little provocative to catch your attention. However, as a Buddhist monk, I have absolutely no interest in taking a defensive or polemical stance. My goal is not to denigrate the God of monotheism, but to explore an idea I found truly liberating. I hope to share this philosophical journey with you in a spirit of open and friendly inquiry.

A Philosopher's Kōan: My Encounter with "The World Does Not Exist"

In my daily life as a monk, I sometimes find that the words of ancient Buddhist scriptures resonate like a kōan—a paradoxical question that vividly shakes up the assumptions we hold in the modern world. It is an intellectual and spiritual experience that dissolves the familiar contours of reality and opens up new horizons for thought. Recently, I had just such an experience, not from a Buddhist text, but from the work of a contemporary German philosopher, Markus Gabriel. The book that opened my mind is titled Why the World Does Not Exist.

This provocative title might at first sound like a nihilistic denial of the very reality beneath our feet. But his argument is nothing of the sort. The "World" that Gabriel argues "does not exist" is not the planet Earth we speak of in daily life, nor is it the "universe" that physics investigates. What he takes issue with is a specific concept that has long been assumed in the history of philosophy: a single, ultimate "container" or "totality" that encompasses everything that exists—from the physical cosmos to numbers, laws, historical events, emotions, dreams, and even gods.

According to Gabriel, such a "domain of all domains," or "the World," cannot exist, not for empirical reasons, but for purely logical ones. The essence of his proof is surprisingly clear. For something to "exist," it must appear in some context, which he calls a "field of sense." A pen, for example, exists in the field of physical objects, while the number "2" exists in the mathematical field of natural numbers. So, in which field of sense does the ultimate container, "the World," appear? By definition, no field can exist outside of it, so it cannot appear in another field. Could it then appear within itself? This is also impossible, because anything that appears in a field is a part of that field, not the field itself. Therefore, "the World" cannot appear in any field of sense, leading to the conclusion that it "does not exist."

This seemingly destructive conclusion, however, is not the final stop for his philosophy. Rather, it is the starting point for a new, constructive vision. What emerges after dismantling the single, monolithic container of "the World" is not a void of nothingness, but an infinite expanse of countless "fields of sense," each with its own inherent rules. The field of the physical universe, the field of mathematical objects, the field of legal relationships, the field of characters in a novel—all these, Gabriel argues, are equally real and cannot be reduced to one another. A unicorn, for instance, does not exist in the biological field of sense, but it certainly "exists" in the distinct field of sense of myths and stories.

This idea is encapsulated in the position he calls "New Realism." It is an attempt to carve out a "third way" between two extremes that tend to bog down modern thought: postmodern constructivism, which claims that no objective reality exists, and scientific reductionism, which posits that reality is exhausted by physical things. New Realism stands on two pillars. First, "realism": we can apprehend things as they are. Second, "pluralism": but there is no single "World" to which all these things belong. This is the core slogan of his philosophy: "realism without the world." By transforming the very definition of existence—by establishing the axiom that "to exist is to appear in a field of sense"—he has completely changed the landscape of ontology. It is a philosophical paradigm shift that liberates our view of reality from a closed, centered universe to an infinite, centerless multiverse.

The Vacant Throne: From the Death of God to the Disappearance of the World

To understand the groundbreaking position Gabriel's thought occupies in the history of Western philosophy, we need to step back and look at the roles played by two key concepts: "God" and "the World." His philosophy can be read as the radical, and in a way, logical conclusion to a story that began with Nietzsche's prophecy of the "death of God."

When the 19th-century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche declared that "God is dead," it was not merely a personal statement of atheism. It was his diagnosis of the collapse of the very structure that had served as the ultimate guarantor of meaning and value for Western civilization for nearly two millennia: the Christian God and the Platonic "true world" that stood behind Him. This loss of a transcendent foundation led Western culture into a profound crisis of nihilism. But philosophy would not allow the "throne of the Absolute" to remain vacant for long.

After God departed, the entity installed on the empty throne was a secularized substitute: the concept of "the World." German Idealism, particularly as represented by Hegel, conceived of "the Absolute" or "the World" not as a replacement for divine providence, but as a self-contained, rationally intelligible totality. This "World" was no longer a transcendent being in the heavens but an immanent reason unfolding within history and nature, and it inherited the role of the ultimate container for all that exists. In this way, theological monism morphed into metaphysical monism and continued to dominate Western thought. If Nietzsche had killed the "lord" on the throne, philosophy simply installed a new one.

It is in this context that the true radicalism of Markus Gabriel's thesis, "the world does not exist," becomes clear. He does not attempt to replace the lord on the throne or to redefine its nature, as much of post-Nietzschean philosophy has tried to do. He demonstrates that the "throne itself" is a logical impossibility. His philosophy is, in a sense, a "second deicide." It is an attempt to logically dismantle the secular successor to God—the concept of "the World" itself, the very structure of a "single, all-encompassing totality."

The consequences of these two "deaths" are starkly different. Nietzsche's "death of God" created a tremendous void and a sense of loss—the crisis of nihilism—because the center of meaning had vanished. Gabriel's "non-existence of the world," on the other hand, does not produce a crisis because it is a logical conclusion. If an all-encompassing container was never logically possible in the first place, then its "absence" takes nothing away from us. On the contrary, once its absence is revealed, we are able for the first time to recognize the shape of an infinitely sprawling, pluralistic reality, untethered to a single center. This is a philosophy not of loss, but of liberation. It is, I believe, a healthy, sane, and well-balanced philosophy.

A Universe of Buddhas and Spirits: A New Philosophy That Affirms Deities

For someone like myself, involved in a religious path, the liberation offered by Gabriel's New Realism is particularly meaningful. It provides a robust philosophical foundation for affirming the "existence" of diverse divinities and spiritualities that have long felt marginalized within the dominant scientific worldview of the modern era.

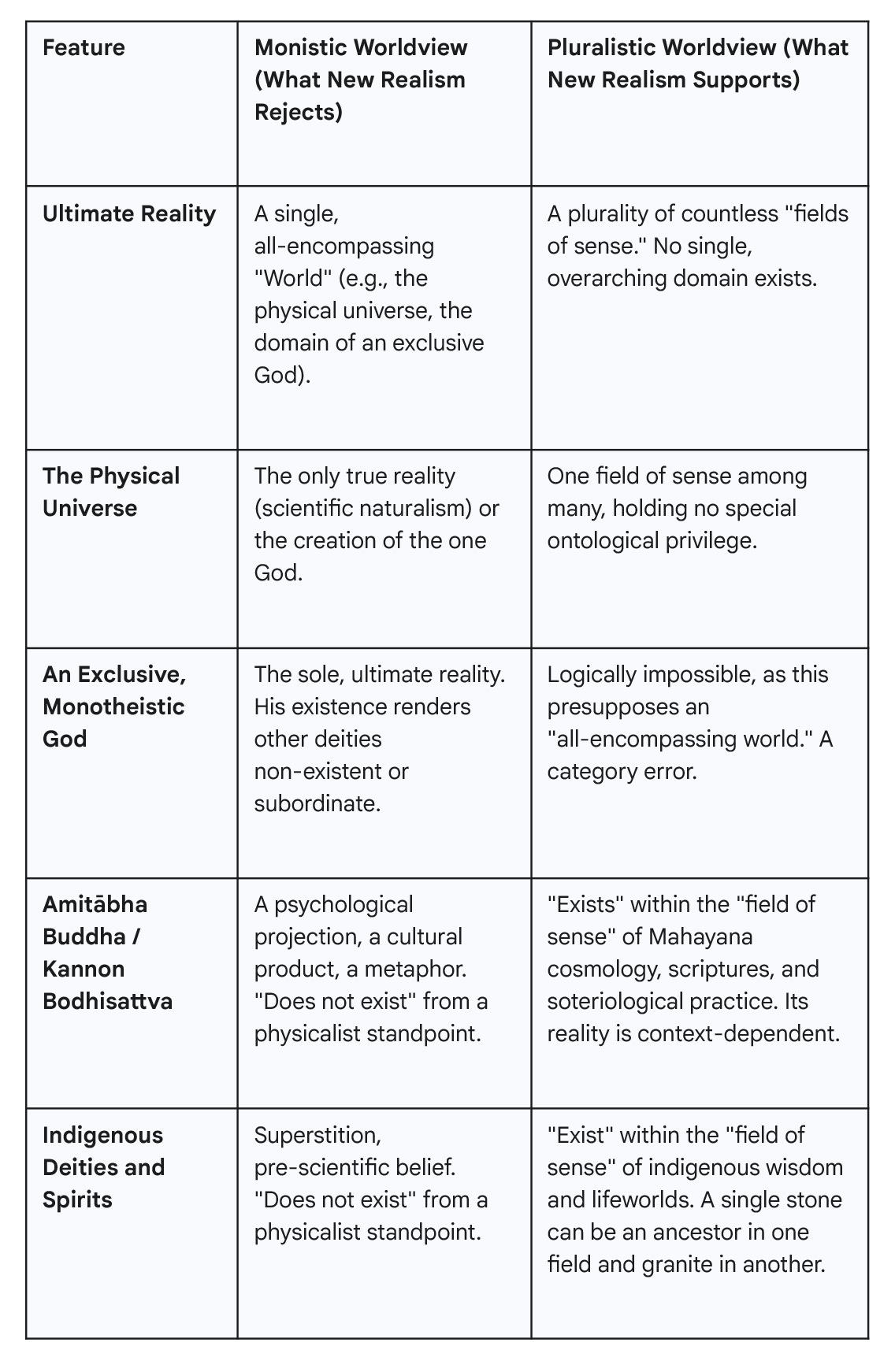

At the heart of his philosophy is a thorough critique of monism. Gabriel harshly criticizes what he calls "fetishism": the attitude of elevating one particular field of sense (for example, the "universe" studied by physics, or the "domain of God" preached by a monotheistic religion) and treating it as the ultimate foundation for explaining all other realities. For him, both scientism (the belief that only science speaks the truth) and exclusive religious dogmas commit the same structural error. They mistake one map of reality out of a countless number for the entire atlas. This kind of narrow vision inevitably gives rise to the idea that "the truth for me must naturally be the truth for you," making conflict unavoidable.

What happens when this monistic view of "the World"—or the idea of a "single, all-encompassing God"—is dismantled? The result is by no means an atheistic void. Rather, it signifies the emergence of a rich space that permits the pluralistic existence of "the gods." Gabriel's philosophy logically denies the existence of a "single God who encompasses everything" while simultaneously supporting the idea that "all deities exist within their own proper fields of sense."

This perspective is incredibly empowering when considering the worldview of Mahayana Buddhism. In Mahayana, there exist innumerable Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and celestial beings, such as Amitābha (Amida) Buddha and Avalokiteśvara (Kannon) Bodhisattva. In our devotional lives, our rituals, and the world of our scriptures, these beings are undeniably real and interact with us. Yet, from a standpoint that absolutizes the singular worldview of the physical-scientific "universe," the "existence" of these buddhas and bodhisattvas is often dismissed as a psychological projection or a cultural metaphor.

Viewed through the lens of New Realism, however, the situation changes entirely. Amitābha Buddha and its Pure Land may not exist in the field of sense of the physical universe, but they unequivocally "exist" within the distinct religious field of sense constituted by texts like the Longer Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra and the devotional practices of Pure Land Buddhism. This is a different kind of existence from physical existence, but it is no less real and possesses its own solid reality. If you were to ask Markus Gabriel, "Does Amida Buddha exist?" I am quite certain he would reply, "Of course! It certainly exists within the field of sense of you Buddhists, just as the universe exists for a scientist."

Furthermore, New Realism offers a useful framework for clarifying an issue that often arises in Jōdo Shinshū (True Pure Land Buddhism): the tendency for people from Christian cultural backgrounds to perceive the relationship with Amida Buddha as being the same as faith in God. Unlike a creator God, Amida Buddha appears and has meaning only in my personal relationship with him, as Shinran said, "It is for me, a single person." There is no nuance here of "something that encompasses all beings." This is another point where New Realism shows a high affinity with Buddhist thought.

This insight resonates deeply with the foundational ideas of Buddhism, especially the Mādhyamaka school's philosophy of "emptiness" (空, śūnyatā), as articulated by Nāgārjuna. Mādhyamaka thought teaches that all things (dharma) are "empty" of a fixed, independent, and substantial essence (svabhāva). Everything comes into being only through its relationship with other things, a principle known as "dependent origination" (縁起, pratītyasamutpāda). Gabriel's assertion that "nothing exists without a relationship to a field of sense" can be seen as a contemporary, Western philosophical expression of this very Buddhist idea of dependent origination. Both philosophies dismantle substance-based monism and present a pluralistic view of reality founded on relationships.

This philosophical perspective sheds new light not only on Buddhism but also on indigenous faiths and so-called animistic worldviews across the globe. As the "ontological turn" in anthropology has shown, much indigenous wisdom is based on an ontology different from that of the modern West—a worldview where humans and nature, matter and spirit, are inextricably linked. For example, the fact that for a certain indigenous people, a particular stone "exists" not as a mere rock but as a living ancestral spirit is, according to Gabriel's philosophy, an objective truth within the unique field of sense formed by that community's culture, history, and rituals. This truth can coexist with, not contradict, the truth that the same object is granite within the field of sense of geology.

In this way, New Realism holds the power to philosophically restore the rich and diverse spiritual realities that have been pushed into the shadows by modern monism. It dethrones the rule of one colossal God and secures a place within our intellect for countless gods and spirits to breathe.

A New Horizon for Dialogue: "I Respect Your Dictionary"

The benefits of this philosophy extend beyond the personal matter of reaffirming the ontological foundation of one's own faith. It also provides a concrete mindset for forging more constructive and respectful dialogue with people of different beliefs.

Traditional interfaith dialogue has often been fraught with difficulty. At its root lay the implicit, monistic assumption that "truth is one." If there is only one true world, then dialogue inevitably takes on the character of a zero-sum game to determine which religion more accurately describes that one truth. In such a context, respecting another's faith could mean compromising the absolute nature of one's own, and dialogue often ended in either superficial friendliness or a stalemate at the impasse of fundamental doctrinal differences.

Gabriel's New Realism, however, overturns the very premise of this dialogue. If "the World" does not exist and reality is a plurality of countless "fields of sense," then the battle over "the one and only truth" loses its very battlefield. The goal of dialogue shifts from deciding who is right to mutually exploring and understanding each other's different, yet equally real, "fields of sense."

When a friend from a Christian background recently asked me, "Does God exist in Buddhism?" I thought about New Realism as I formulated my answer. For me, living within a Buddhist worldview, the personal, creator "God" of the Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam) is not a main entry in my faith's dictionary. But when I speak with my Abrahamic friend, a New Realist mindset allows me to adopt the following attitude:

"The term 'God' isn't a primary entry in my dictionary. However, I deeply respect that in your dictionary, that word is on the very first page as the most important entry of all. I would love for you to tell me more about it—about how that entry defines all the other words in your dictionary and how it gives order and meaning to your world."

This stance is not mere tolerance or relativism. It is grounded in "ontological respect"—the acknowledgment that my friend's world of faith is objectively real as a "field of sense" for them. "God" is real for my friend with the very same certainty that Amida Buddha is real for me. When we stand on this point of mutual recognition, we can, for the first time, take a sincere interest in the core of another's faith without feeling that the core of our own is threatened. It is a dialogue for true learning and understanding, not for conversion. This philosophy creates a gentle and intelligent space where those of us with different dictionaries can bring them together and become richer for it.

Echoes of Faith: On the Wish, "But the World Must Exist"

Finally, I would like to explore a notion that has begun to sprout within me at the end of this philosophical journey with New Realism. It is the realization that, in the critiques of this philosophy, we might find a light that illuminates the very essence of "faith."

The most common, and perhaps most persistent, objection that many people have to Gabriel's thesis is a strong, intuitive resistance: "That can't be right. It's just wordplay or a category mistake. Surely, an all-encompassing world must still exist."

While there are many ways to respond to this on a professional philosophical level, what I want to focus on here is not the logical validity of the objection, but the feeling behind it. Why do people want to insist so strongly that "the world exists"? Even after Gabriel's argument demonstrates the logical impossibility of "the World" as an all-encompassing container, what is this powerful impulse that makes one feel, "And yet, something that includes everything must exist, and I want it to exist"?

It seems to me that here we see at work a kind of "leap of will" from the depths of the human spirit. It is the feeling that there is "something" one wants to believe in, even if it means going beyond logical consistency or making a logical jump. Is this not a primal thirst for an ultimate order or unity behind all the fragmented, countless realities—something that would integrate them all into a meaningful whole?

Traditionally, has humanity not used the word "faith" to describe this very kind of trust in and commitment to an ultimate reality that transcends logic? If so, then perhaps the very people who most strongly resist Gabriel's philosophy—those who feel compelled to insist that "the world still exists"—are, ironically, the ones who embody the structure of "faith" in its purest form. Their claims may be couched in secular (and technical) terms rather than religious ones, but at their root, one can almost hear a wish that resembles an earnest prayer: "I want the world to be a single, meaningful whole."

Markus Gabriel's philosophy dismantled "the World," the secular successor to God. But what was left after this deconstruction was not a cold void, but rather the fundamental question of why human beings cannot help but seek unity and totality. By taking away our easy answers, his philosophy may, in turn, hold up a mirror to the "craving for faith" that lies within us. To gaze quietly into that mirror—perhaps that, too, can be a profound form of religious practice in our time.