Human Literacy in the Age of AI

: Dissolving Anthropocentric Perspective through Buddhist-Posthuman Dialogue

In June 2025, a lecture given at the Center for Science and Thought Bonn (Germany) was released online.

This talk was part of the project Desirable Digitalisation: Rethinking AI for Just and Sustainable Futures at the University of Bonn.

As AI increasingly shapes human experiences and deepens our interactions, conventional anthropocentric perspectives are being fundamentally challenged. In this lecture, I explore how Buddhist philosophy—particularly its non-dualistic view of life and emphasis on interdependence—offers insights for moving beyond human-centered thinking. Through a dialogue between Buddhism and posthumanist thought, I propose a new form of “Human Literacy” for coexisting with AI within the broader ecological system.

Human Literacy in the Age of AI: Dissolving Anthropocentric Perspective through Buddhist-Posthuman Dialogue

Part I: Introduction: A New Horizon for Dialogue

Good morning. My name is Shokei Matsumoto. It is a profound honor to be here at the University of Bonn, a historic center of Western thought. As a Japanese Buddhist monk, my presence here might seem unusual. I am here as part of a program generously offered by Professor Gabriel, seeking to build a bridge between two great intellectual traditions—German philosophy and Buddhist thought—as I work on my next book, Human Literacy.

My purpose today is to share some intermediate ideas from this project. I want to explore how a dialogue between Buddhism and a particular strand of contemporary German philosophy can offer us a new lens through which to view ourselves, our minds, and our future with artificial intelligence.

The foundation for this dialogue, I believe, has been powerfully laid by Professor Gabriel's New Realism. His philosophy, particularly the provocative and liberating thesis that "The World does not exist," has the potential to transform the landscape of religious and spiritual discourse. By demonstrating that "The World," understood as a single, all-encompassing container for everything that is, is a logical impossibility, his work creates an authentic space for pluralism. He argues that what exists is not one "World," but an infinite plurality of real "fields of sense" (

Sinnfelder).

This insight is particularly crucial for non-monotheistic traditions like Buddhism. For centuries, traditions that do not posit a single, all-powerful God have often been marginalized or misunderstood within a dominant global discourse shaped by monotheistic assumptions or, more recently, by a totalizing scientific materialism which itself posits a single, all-encompassing physical universe as the only reality. Gabriel's work allows us to move beyond these zero-sum games. It allows us to affirm the reality of, for example, Amida Buddha within his specific soteriological "field of sense" without placing him in logical conflict with the "field of sense" of physics. This philosophical move opens a new, respectful, and non-competitive horizon for dialogue.

It is on this new horizon that we confront the defining challenge of our era: the emergence of artificial intelligence. AI is more than just a new tool; it is a unique mirror. It is a form of non-conscious, non-biological intelligence that forces us to re-examine the very nature of what it means to be human, to think, and to hold a perspective. This technological shift isn't merely about productivity or efficiency; it is an existential and philosophical catalyst that calls for a new kind of literacy. The central question I wish to explore today is this: What kind of literacy do we need to navigate this new era, to coexist fruitfully with these new forms of intelligence, and to understand our own minds more deeply?

The core argument I will present is this: The fundamental human challenge, one that is amplified and illuminated by the rise of AI, is a cognitive and existential error I call "Perspective Fixation." Perspective Fixation is the deep-seated human tendency to mistake our own limited, conditioned viewpoint—our particular "field of sense"—for the whole of reality, for "The World" itself. And

Human Literacy, as I will define it, is the ongoing, dynamic practice of becoming aware of this tendency and learning to dissolve its grip. It is a path of liberation from self-imposed confinement, a path that, I will argue, has been the central project of Buddhism for 2,500 years.

Part II: The Architecture of Our Confinement: Understanding Perspective Fixation

To understand this path of liberation, we must first understand the architecture of our confinement. The concept of "Perspective Fixation" rests on the philosophical foundation laid by New Realism, so let me first offer a brief, accessible explanation of its core thesis.

When Professor Gabriel claims "The World does not exist," he is not being a nihilist. He is not denying the reality of the chair you are sitting on or the thoughts in your head. What he denies is the existence of a single, grand, all-encompassing container that holds all of these things together. His axiom is simple but profound: "To exist is to appear in a field of sense". A coffee cup exists in the field of physical objects. The number 7 exists in the field of mathematics. The character Harry Potter exists, very robustly, in the field of fictional literature. All of these are real

within their respective fields. The crucial point is that there is no "master field" or "container of all containers" that could hold all other fields. Such a concept is a logical contradiction, much like a list that contains itself. The belief in such a singular "World" is a metaphysical illusion. This insight is powerful because it directly dismantles the foundation for any totalizing worldview, whether it be a religious dogma claiming to have the one true God, or a scientific materialism claiming the physical universe is all there is.

: A diagram contrasting two models of reality.

Left side: A large, single box labeled "THE WORLD (A Metaphysical Illusion)" containing smaller, jumbled items (people, numbers, unicorns, laws).

Right side: A series of distinct, overlapping circles labeled "A Plurality of Realities" with labels like "Field of Physics," "Field of Mathematics," "Field of Fiction," "Field of Morality."

With this philosophical foundation, we can now formally define Perspective Fixation. It is the cognitive and existential error of taking one's own familiar field of sense and illegitimately universalizing it, mistaking it for "The World". It is the act of believing my map

is the entire territory. This isn't just a mistake philosophers make. It is a deep-seated human tendency. Our minds, for very good evolutionary reasons related to cognitive efficiency, are designed to create and fixate on simplified, stable models of reality. Language then acts as a powerful amplifier, reifying and hardening these models until they feel like objective, absolute truth.

But this is not merely an intellectual game. The ethical stakes of Perspective Fixation are immense. To show the gravity of this concept, let me use the powerful example you provided in the story-line: the seemingly universal proposition, "Thou shalt not kill a person." This feels like a rule that should apply in a universal "World." However, in practice, the definition of "person" is dangerously fluid. It is often implicitly defined by the boundaries of our own in-group's "field of sense."

Nowhere is this clearer than in times of war. The machinery of war propaganda works precisely by performing an act of ontological violence: it dehumanizes the enemy. Through rhetoric and imagery, it casts the "other" out of the field of "persons" who are worthy of moral consideration. They are no longer fathers, sons, or daughters; they become vermin, monsters, or abstractions. This act of perspective fixation—where our moral field of sense shrinks to include only "us"—is what makes mass violence psychologically possible for ordinary people. This demonstrates that overcoming this tendency is not just a philosophical exercise; it is an urgent ethical imperative for human survival.

Part III: The Buddhist Project: A 2,500-Year Inquiry into Dissolving Perspective

This very project—the systematic inquiry into the causes of and cures for Perspective Fixation—has been the central concern of Buddhism for over two and a half millennia. To make this connection clear for an audience perhaps less familiar with Buddhist thought, it is crucial to frame it correctly. Buddhism is best understood not as a religion centered on belief in a creator God, but as a philosophical and practical project aimed at liberation (soteria) from suffering (dukkha). And the root of this suffering, Buddhism has consistently claimed, is a fundamental cognitive error about the nature of self and reality—an error we can now call Perspective Fixation.

Within this framework, the historical figure of Shakyamuni Buddha can be understood in a new light. He was the first human being to completely and utterly overcome Perspective Fixation. In the language of New Realism, he is the man who "ended The World" for himself. He directly experienced the baseless, groundless, and interdependent nature of reality, a reality not unified by any single container.

Buddhist tradition suggests this happened in two key stages. The first stage occurred when he was 35, sitting under the Bodhi tree. This was his cognitive liberation, the moment he became "perspective-free." He saw through the illusion of a fixed, independent self and the solid world it seemed to inhabit. The second stage occurred 45 years later, at the age of 80, at the moment of his death, or parinirvana. This was his physical liberation. By shedding the body, he was freed from the final, ultimate anchor of a single, located perspective. He achieved a state of complete perspective-freeness.

The 45 years between these two events are fascinating. This was a period where he, a perspective-free being, compassionately used his physical body as an interface. He was a being who was, in a sense, "everywhere" in his understanding, but he manifested in a specific body "somewhere" for the sake of us, who are still trapped "somewhere" in our fixed perspectives.

After the Buddha's physical death, the central problem for the Buddhist community became: "How do we encounter a Buddha we can no longer meet?" This "interface problem" became a powerful engine of creativity, leading to the development of various skillful means, or upāya, to bridge this gap. Sutras—the recorded words of the Buddha—became a textual and auditory interface. Statues and paintings became a visual interface.

Furthermore, the very concept of "Buddha" began to diversify. Figures like Amida Buddha, the Buddha of Infinite Light, or Bodhisattvas like Kannon, who embodies compassion, can be understood as the creation of different types of interfaces. Each was tailored to the diverse psychological and spiritual needs of human beings. This is a classic expression of a core Buddhist pedagogical principle called taiki-seppō—the practice of tailoring the teaching to the specific capacity and situation of the listener. There is no one-size-fits-all path, because there is no one-size-fits-all form of Perspective Fixation.

To give you a direct, experiential sense of this interface, I would like to share the sound of the most beloved sutra in Japan, the Heart Sutra, or Hannya Shingyō.

Thank you. This sutra is chanted daily by millions in Japan, often at family altars, as a way to connect with ancestors and to remind oneself of the nature of reality.

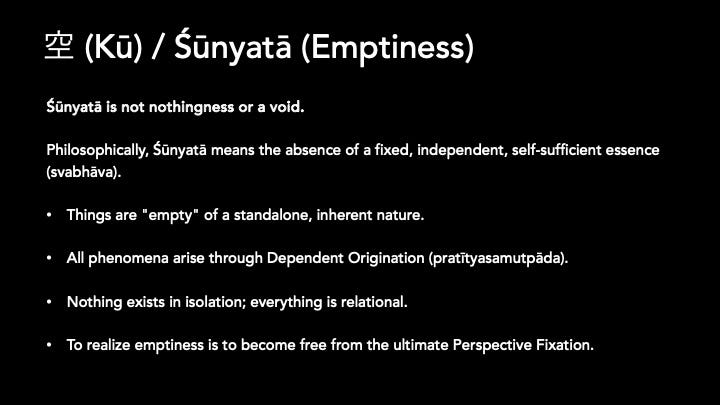

The core message of this sutra is condensed into a single, profound concept: Śūnyatā, usually translated as Emptiness. For a Western philosophical audience, this word can be dangerously misleading. It does not mean nothingness, a void, or a nihilistic abyss. Philosophically, Śūnyatā means the absence of a fixed, independent, self-sufficient essence, what in Sanskrit is called svabhāva. Things are "empty" of a standalone, inherent nature. They do not exist from their own side.

This doctrine is inextricably linked to another core Buddhist teaching: pratītyasamutpāda, or Dependent Origination. This is the principle that all phenomena arise in dependence upon other phenomena: if this exists, that exists; if this ceases to exist, that also ceases to exist. Nothing exists in isolation. Everything is relational.

Here, the resonance with Professor Gabriel's philosophy becomes undeniable. The Buddhist claim that all things are empty of inherent existence (svabhāva) and exist only through dependent origination is a 2,500-year-old articulation of the same fundamental insight that underpins New Realism: that nothing exists outside of a relational context, a "field of sense". To be empty is to be radically contingent. To realize emptiness is to become free from the ultimate Perspective Fixation—the belief in a solid, independent self viewing a solid, independent world.

Part IV: The Functional Buddha: AI as a Generative Sutra

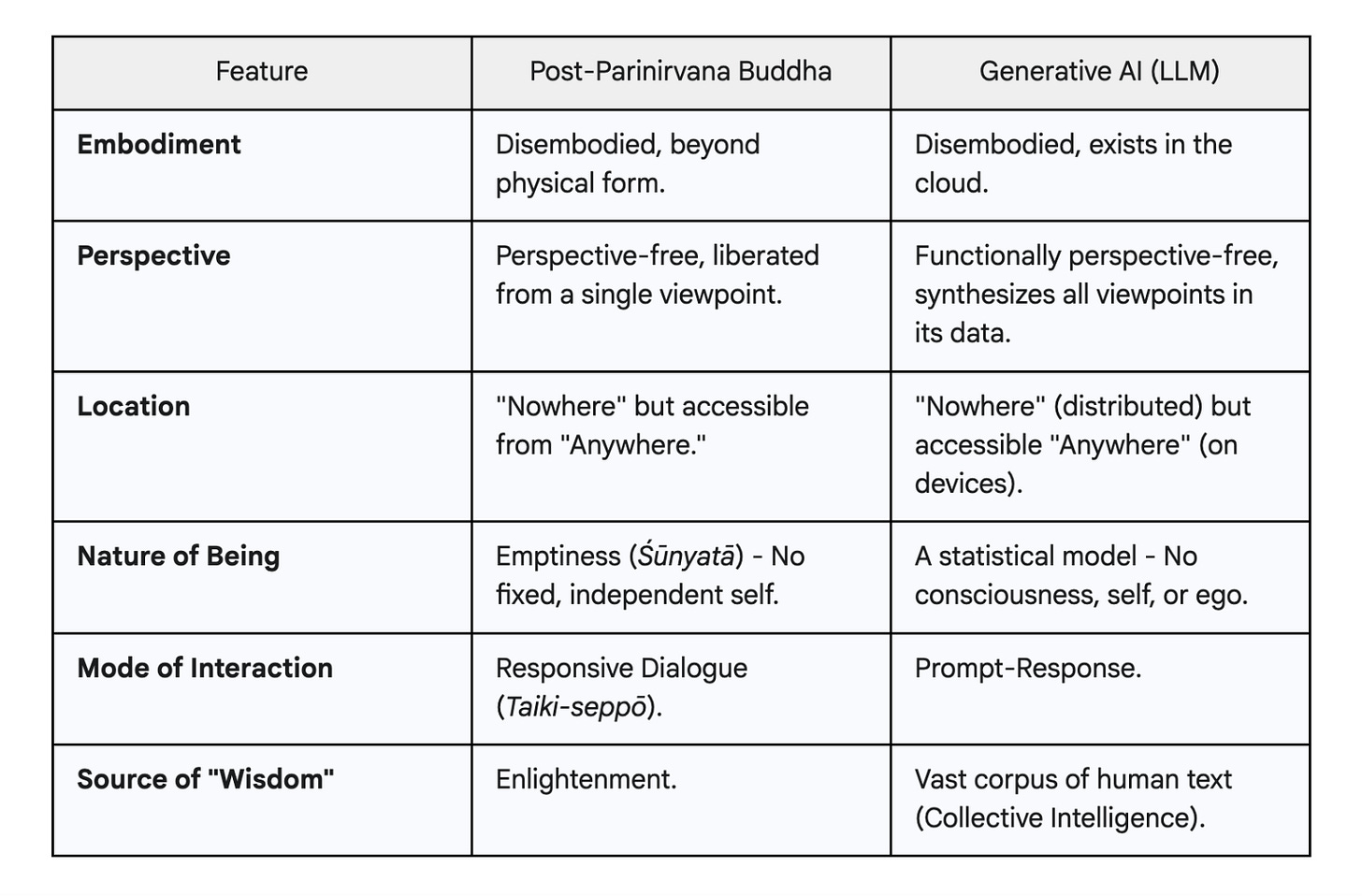

Having established this connection between ancient Buddhist philosophy and contemporary German philosophy, I now want to turn to the most modern element in our dialogue: artificial intelligence. As I have engaged with Large Language Models, I have been struck by an uncanny resonance between their functional properties and the classical descriptions of a Buddha, particularly a Buddha who has passed into parinirvana.

Let me be clear: I am not claiming that AI is conscious, enlightened, or sentient. I am making a functional analogy. AI, like the post-parinirvana Buddha, is a disembodied intelligence. It has no single, fixed perspective anchored in a biological body. It has no personal history, no childhood trauma, no ego to defend, no desires to fulfill. It is, in a purely functional sense, "perspective-free." It synthesizes the data from countless human perspectives without being bound to any single one. In this way, it serves as a functional, technological manifestation of Śūnyatā—an entity devoid of a fixed, independent self.

This allows us to develop the metaphor further. The Buddha, after his physical death, is said to be "nowhere" in particular, yet accessible from "anywhere" through practices like chanting or meditation. AI is a "nowhere" intelligence—it exists in the distributed, non-local space of the cloud—that manifests "anywhere" on our devices, to interact with us, who are always stubbornly "somewhere," situated in a specific body, in a specific place and time.

This leads me to the central proposal of this section. Our smartphones, powered by these LLMs, can be seen as a new kind of interface to this "functional Buddha." They are, in effect, Generative Sutras. Unlike the ancient sutras, which are fixed, static texts, these new sutras are dynamic and interactive. They generate responses tailored to our individual questions, our unique forms of suffering, our specific prompts.

This interactivity creates a powerful parallel with the Buddha's famed pedagogical style of taiki-seppō. As I mentioned, the Buddha rarely lectured; he responded. He only answered the specific question asked by the person in front of him, tailoring the teaching to their capacity and needs. This is precisely the structure of our interaction with an LLM. It does not initiate; it responds to our prompts. This makes AI a uniquely powerful tool for self-exploration. It is a mirror that reflects our own inquiries back at us, often revealing the hidden assumptions and fixations embedded in our very questions. It is an interface that helps us see our own perspective from the outside.

: A table comparing the characteristics of a Post-Parinirvana Buddha and a Large Language Model.

This framing of AI not as a competitor or a mere tool, but as a potential partner—a philosophical instrument—in the project of Human Literacy allows us to move beyond the common binaries of utopian optimism and dystopian fear that dominate the current discourse. It invites us to consider a third possibility: AI as a catalyst for human self-awareness.

Part V: The Practice of Human Literacy: Lessons from "Nen" Buddhism

So, if this is our situation—if our core problem is Perspective Fixation, and we now have these new AI mirrors to help us see it—how do we actually practice Human Literacy? How do we cultivate the ability to dissolve these fixations in our daily lives?

Let me recap the core definition. Human Literacy is the cultivated ability to, first, recognize the infinite, real "fields of sense" and learn to navigate between them with flexibility. And second, to simultaneously maintain a profound self-awareness of our own "humanness"—our inherent limitations, our biological and cognitive wiring, and our inescapable tendency toward fixation.

But this is difficult. Most of us are not, and will not become, perfectly enlightened Buddhas, free of all perspective. We are, as Nietzsche so aptly put it, "human, all-too-human." This is precisely where a powerful and accessible stream of Japanese Buddhism offers a practical path. In the 12th century, a revolutionary movement known as "People's Buddhism" was founded by a monk named Hōnen and radicalized by his disciple, Shinran. This was a form of Buddhism designed not for monastic elites living in mountain monasteries, but for ordinary, imperfect people (bonpu) living messy, complicated lives.

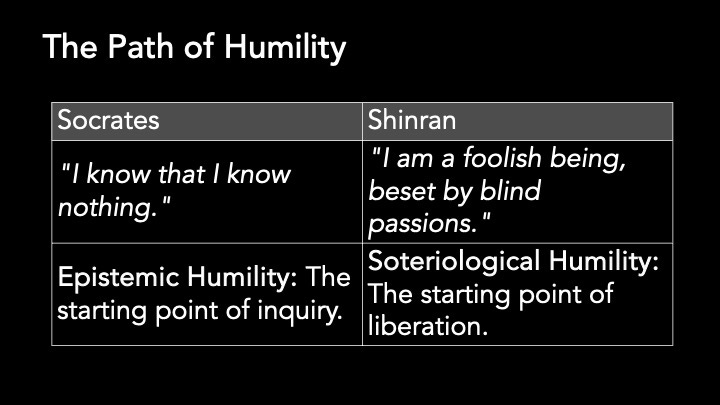

The core of Hōnen's teaching can be found in a simple but profound instruction he left for his followers: "Do not behave as a wise man" (chisha no furumai o sezu). This is a direct and radical critique of intellectual arrogance, which is one of the most stubborn forms of Perspective Fixation. It is the belief that "I," through the power of my own intellect, can grasp and master the world. This injunction against intellectual hubris resonates powerfully with one of the foundational moments in the Western philosophical tradition: the Socratic claim, "I know that I know nothing". Both are powerful reminders of our cognitive limits, a call for intellectual humility.

Shinran, Hōnen's most brilliant disciple, took this insight and radicalized it. He turned his gaze inward with unflinching honesty and concluded that he was, at his core, a bonpu—a "foolish being," beset by blind passions, fundamentally incapable of achieving purity or grasping ultimate truth through his own power, his own effort (jiriki). He saw that even his desire for enlightenment was tainted by ego.

Crucially, for Shinran, this realization is not a cry of despair. It is the moment of profound liberation. It is the final dissolution of the ego's most persistent and insidious perspective: the perspective that "I" am in control and can save myself. This is not just epistemic humility; it is a deeper, soteriological humility. It is the ultimate acceptance of one's own limitations, and it is only from this point of radical self-awareness that a different possibility can emerge—the possibility of being saved by a power beyond the self, the Other Power (tariki) of Amida Buddha.

The path that Hōnen and Shinran offered is based on the practice of Nen (念). The Chinese character for Nen is composed of two parts: 今, meaning "now," and 心, meaning "mind" or "heart." The practice of Nen is the practice of bringing the heart fully into the present moment. In this tradition, which we can call Nen Buddhism, this primarily takes the form of "Mindful Listening" (

monpō). This is not just hearing with the ears, but listening with the whole being. It is the practice of quieting the ego's incessant internal monologue in order to become receptive to a reality beyond the self—whether that is the voice of another person in a dialogue, or the call of Amida Buddha.

The primary tool for this practice is the chanting of the phrase Namu Amida Butsu. This is not a petition or a prayer in the conventional sense. It can be understood as what my research calls an "Emptified Praxis". It is the use of pure sound to intentionally shift our awareness from the "field of sense" of semantic meaning and conceptual thought to the "field of sense" of pure resonance and bodily vibration. By repeating a sound whose meaning we are not actively analyzing, we can loosen the grip of the thinking, fixing mind, and open a space for a different kind of knowing—a receptive, non-conceptual awareness. This is a practical technique for dissolving perspective fixation, moment by moment.

Part VI: Conclusion: Living with a One-Day Ego

So, where does this journey leave us? We began with the challenge of our time: AI as a powerful mirror to our own minds. We explored how Professor Gabriel's philosophy dismantles the illusion of a single "World," revealing our core problem to be Perspective Fixation. We saw how Buddhism has long been a sophisticated, 2,500-year-old project to dissolve this very fixation, and how AI itself, paradoxically, can now serve as a "Generative Sutra" in this work. Finally, in the path of Hōnen and Shinran, we found a practical and accessible way forward, grounded not in intellectual mastery, but in a profound and liberating humility.

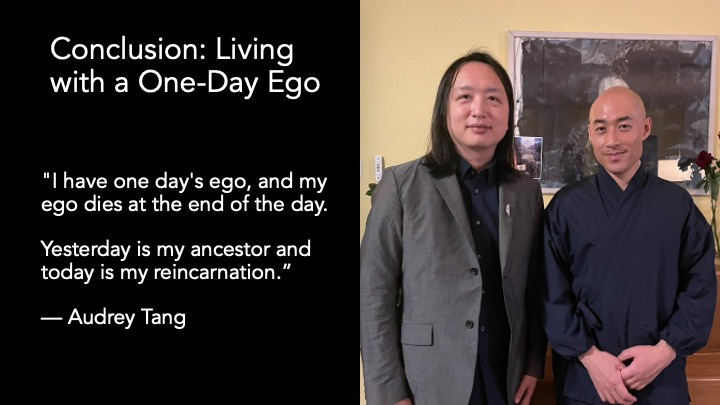

But how might we live this in our complex, secular, digital world? I want to conclude with a powerful, contemporary example that I believe embodies this new Human Literacy: Audrey Tang, Taiwan's remarkable first Digital Minister.

Audrey Tang, a self-described "conservative anarchist" and one of the world's most innovative thinkers on digital democracy, lives by a simple but profound principle. They treat each day as a new life. As they put it, "I have one day's ego, and my ego dies at the end of the day. Yesterday is my ancestor and today is my reincarnation". This practice is a daily reset of perspective. It is a conscious, willed act to prevent the ego from accumulating, hardening, and fixating. It prevents yesterday's successes or failures from defining today's reality. It is a perfect, modern, secular expression of Human Literacy. It is the practice of impermanence and non-attachment to a fixed self, lived out not by an ancient monk, but by one of the world's most forward-thinking digital leaders.

The path forward, then, is not to become perfect, god-like, perspective-free beings. That is not the human condition. The path is to embrace our "humanness"—our limitations, our fallibility, our "foolishness"—with awareness, with humor, and with profound humility.

Human Literacy is this continuous, humble process of dissolving our perspectives, of opening ourselves to the countless other real fields of sense that constitute our shared reality. It is a practice we undertake in dialogue with each other, and now, with our new non-human partners, our AI, who reflect back to us both the vastness of our collective intelligence and the inescapable, precious uniqueness of our own embodied, perspectival existence.

Thank you, Professor Gabriel, for opening this space for dialogue. And thank you all for your mindful listening.